Long before meeting a barefoot, breathless, nuggety man on the

steps of the Brookfield show grounds in 1996, it was clear to us

we had a responsibility to survive this millennium drought (as

we now know it) and steward our brittle farm. We had already

followed the love of nature we both found in our infancies and

childhood through to environmental protests and reading Grass

Roots in our teens. Bill Mollison said everything that we knew

innately.

We are not superior to other

life forms and there are only solutions that lie within the

problems. We knew the protracted and thoughtless labour of the

average Australian farm needed to stop. The dedicated rural

people needed to have the space, education and inclination to

take a thoughtful observational perspective at the plants and

animals, soil and the people in landscapes so we could steward

natural systems and still provide clean clear environments for

future generations.

Forward to another drying and

death filled post-flood era, where we realised we needed to

plan the heck out of what we were going to do for the next

battle: to take it into the more impending doom of Climate

Change. We were very lucky to be offered a place with the

local Landcare on a six-session weekend course with

Rodger Savory .

Holistic Planning made sense to

us. I think at the time we sat down each weekend as a family and

were in complete amazement at how it is what we had been looking

for. We consisted of two very nerdy farmer women who loved lists

and analysis and being pragmatically hardworking, a very

creative, nature loving, practical and philosophical dreamer who

didn’t really like farming and an already half worn son who was

all those other things but also wanted to be able to get up each

morning and make a difference to production and environment in a

meaningful way... a hard ask in drought. Coming out of that

course we knew ourselves a little more and were questioning

everything with a more solid state of mind and a forward plan.

Concepts like the seven holistic decision-making questions were

used on everything. Unlike other farm planning courses, we had

done way back when, it made us take out our heart and brain and

think with our souls on what we truly wanted for our lives and

the context in which we lived. Not just why we have chosen to

live but where we live and why. Deeper meanings being sought,

and it in turn relates to place and work and relationships.

Start with the bigger whole. This is you. The hard part came

when the brain and hearts were put back in. My holistic context

was simple. “I need

to live my life everyday with direct purpose and meaning. Caring

for and being cared for by loved ones, my community, my

environment and my planet”

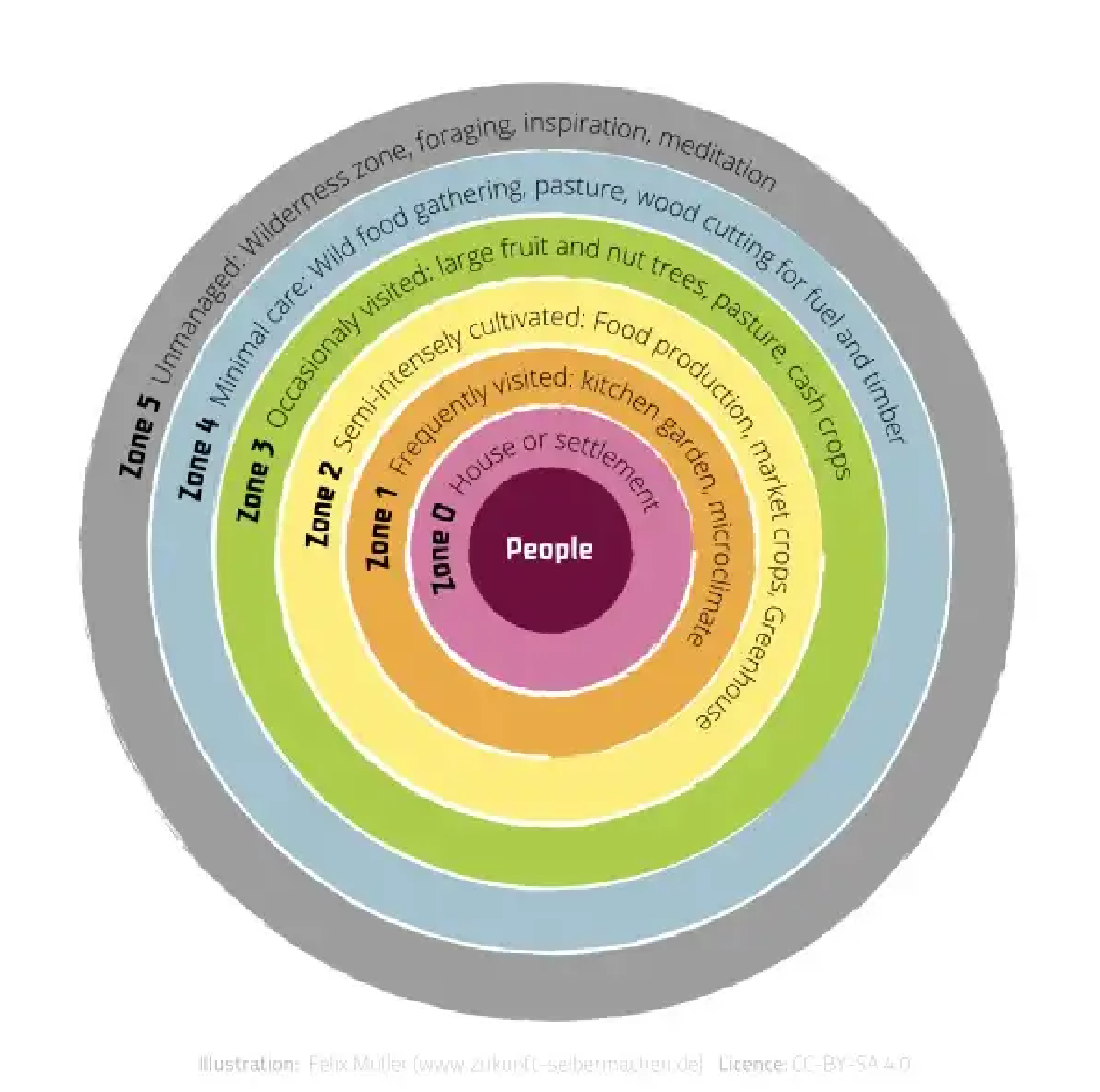

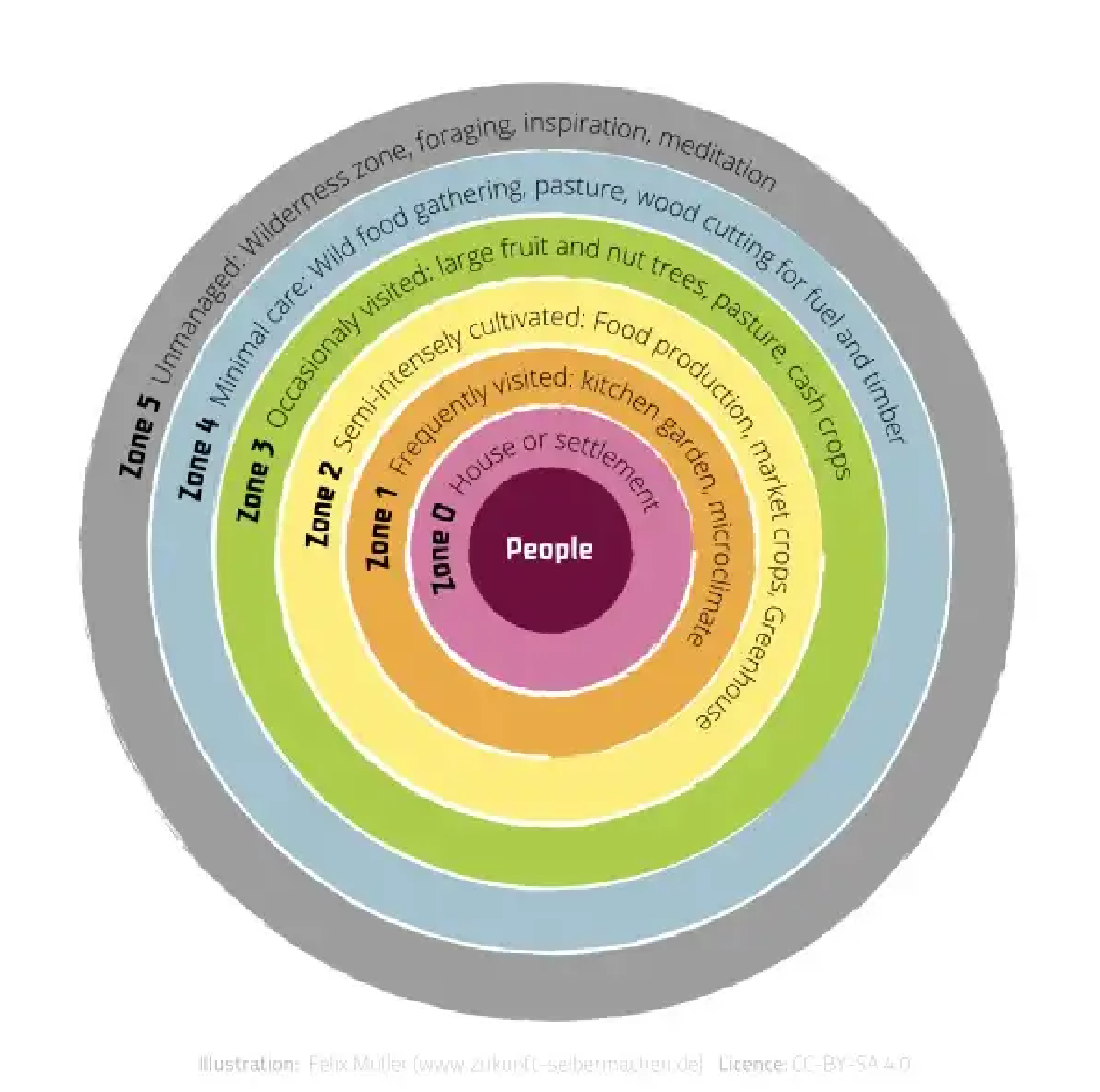

See this good resource: https://deepgreenpermaculture.com/permaculture/permaculture-design-principles/4-zones-and-sectors-efficient-energy-planning/

See this good resource: https://deepgreenpermaculture.com/permaculture/permaculture-design-principles/4-zones-and-sectors-efficient-energy-planning/

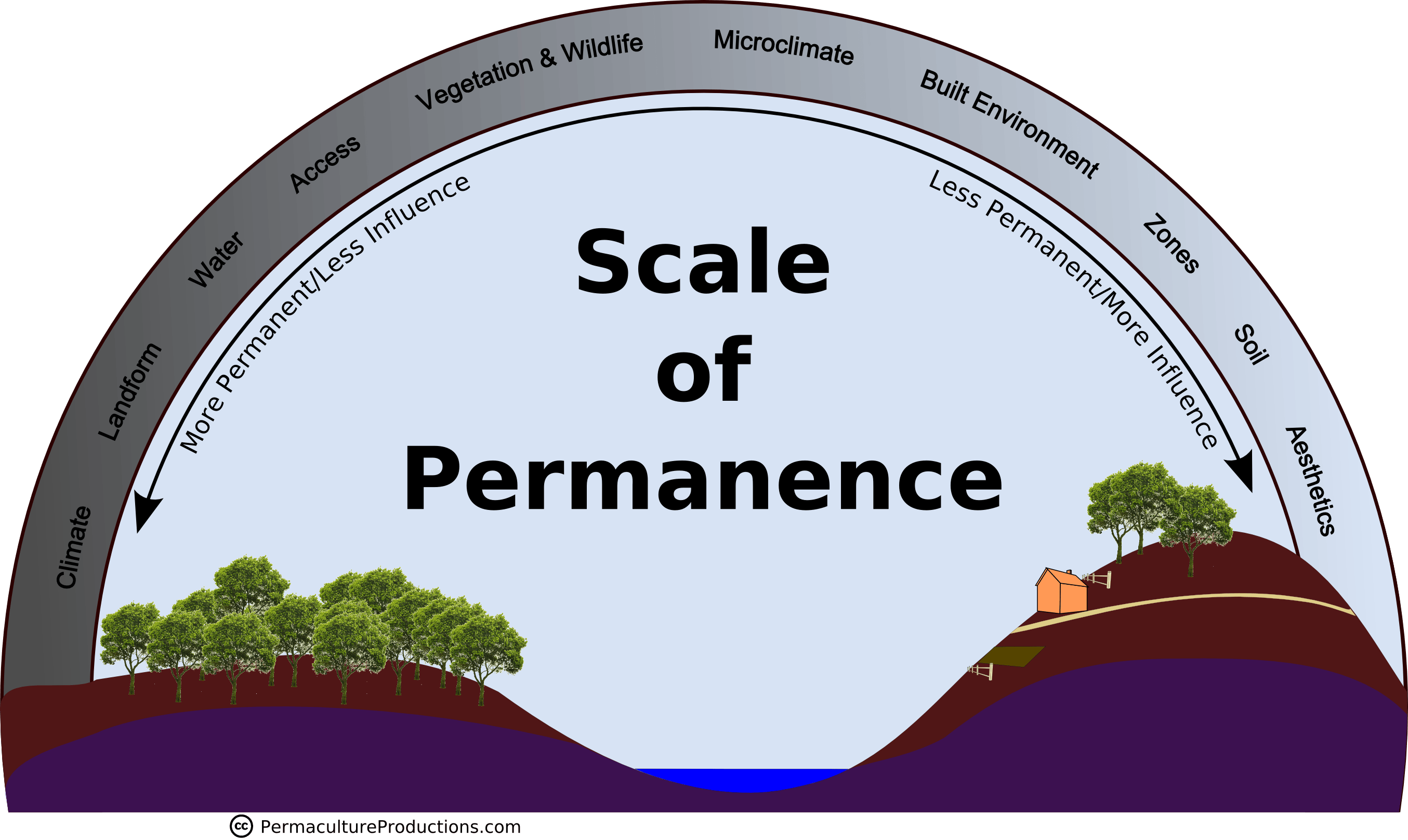

The first on this scale is climate. I am stuck with my

climate as I chose to live here. Our farm is a family farm

with history and many positive attributes that means we

wouldn’t choose elsewhere. You can’t change climate as an

element that is entering the site. You can mitigate its

affects and make use of it. We also must be highly adaptive

to the ever-changing seasons that will occur over the next

few decades. Our area is predicted to have more drought,

more intense rain events including storms and the jury is

still out on the winters. Could be warmer, most likely

colder and drier. Presently we can only observe that the

periods of time without rain are longer. Our spring is now

filled with heat waves and dry wind and our summer rain has

now been pushed back to late January at the earliest. Our

market garden site was chosen for the beautiful black soil

that is self-mulching and very fertile. It has a well fenced

2 acres away from wildlife and no terrain problems. Most

organic market gardeners would think it a blessing. That it

is, but what we sometimes see as the best options can have

other implications. Weather wise, the site is okay in summer

but without shade and very cold in the winter (minus 9

minimum for at least 3 nights a year). The worst winds come

from the west in winter and the north in a droughty spring.

The sun is becoming too intense for constant commercial

vegetable production in summer.

How have we ‘fixed’ these issues? Well, we put up hoop

houses made out mostly recycled materials and either

reusable or second-hand. Big tick. They are great for pests

and mitigating climate effects. We have five all up on the

property so far. At the market garden site, we have two. Our

priority is that they all pay for themselves in full cost

accounting before the next goes up but at the time of

writing we really need more. The last paid for itself within

two months in cost of production verses output but it was

made partially out of steel, so we always consider the

long-term environment effects of that decision to use a

non-renewable resource. We put up shade sails to counter the

wind and shade problems. That worked very well until the

hailstorm event of November 2020 that wore some down and

damaged others and the plants beneath. To be fair, it

wrecked the hoop house production, which was ramping up

production coming out of spring. We have experimented with a

whole array of plants. Despite the minus nine winters, sugar

cane is a stayer as is mugwort. Mugwort is very greedy and

has some invasive roots which are allopathic. I have tried

pigeon peas which are a subtropical favourite here but must

treat them as an annual. They provide a great shade and

legume mulch. Leucaena is a goer too but must be treated

again as a plant that will grow forth in spring and then

maybe gain enough ground in summer to endure the winter.

These plants protect, mulch and modify microclimates. At

time of writing, I am yet to try Tagasaste and Russian

Olives as hedgerow plants that can survive the winters and

be happy in the summers. My mind’s eye sees hedgerows of

shade and wind protection but unfortunately only a summer

reality at this stage. We have experimented with more

physical structures and have put up insect walls made of

wood that have helped. They have been a great experiment so

far in that we have lizards and solitary bees, spiders and

eggs of beneficial insects. This summer we plan to use more

recycled hail damaged shade cloth to create more shade/wind

breaker walls in our long beds. Landforms are also something

we can play with on a micro scale. It is next on the list of

top three things we need in place first in planning. They

are climate mitigators too. Protection and water gathering

for rainwater harvesting. Our place has lots of terrain and

some we can play with for water and fertility capture. Our

market garden site is on a fence line bordering our

neighbours where we share a flat valley floor which in an

ideal world would maybe not be demarcated by ownership or

fences. It is on about a one-degree slope downhill towards

our garden. We installed a swale to feed nutrient and water

into the second hoop house and to establish a line of

mulberries that will shade and drop very nutritious leaves

into the swale for extra downhill nutrition. Swales have

been very successful on other parts of the property

including the first hoop house we built which post rain

event requires only a light watering for even intensive

crops and the fertility is building year after year. Another

swale is being constructed for bamboo and more mulberries.

Micro swales have been included when planting a small

orchard on site too. We have also planned for the top of our

swale to have composting bins that will take any nutrient

run off to the lower part of the garden.

How have we ‘fixed’ these issues? Well, we put up hoop

houses made out mostly recycled materials and either

reusable or second-hand. Big tick. They are great for pests

and mitigating climate effects. We have five all up on the

property so far. At the market garden site, we have two. Our

priority is that they all pay for themselves in full cost

accounting before the next goes up but at the time of

writing we really need more. The last paid for itself within

two months in cost of production verses output but it was

made partially out of steel, so we always consider the

long-term environment effects of that decision to use a

non-renewable resource. We put up shade sails to counter the

wind and shade problems. That worked very well until the

hailstorm event of November 2020 that wore some down and

damaged others and the plants beneath. To be fair, it

wrecked the hoop house production, which was ramping up

production coming out of spring. We have experimented with a

whole array of plants. Despite the minus nine winters, sugar

cane is a stayer as is mugwort. Mugwort is very greedy and

has some invasive roots which are allopathic. I have tried

pigeon peas which are a subtropical favourite here but must

treat them as an annual. They provide a great shade and

legume mulch. Leucaena is a goer too but must be treated

again as a plant that will grow forth in spring and then

maybe gain enough ground in summer to endure the winter.

These plants protect, mulch and modify microclimates. At

time of writing, I am yet to try Tagasaste and Russian

Olives as hedgerow plants that can survive the winters and

be happy in the summers. My mind’s eye sees hedgerows of

shade and wind protection but unfortunately only a summer

reality at this stage. We have experimented with more

physical structures and have put up insect walls made of

wood that have helped. They have been a great experiment so

far in that we have lizards and solitary bees, spiders and

eggs of beneficial insects. This summer we plan to use more

recycled hail damaged shade cloth to create more shade/wind

breaker walls in our long beds. Landforms are also something

we can play with on a micro scale. It is next on the list of

top three things we need in place first in planning. They

are climate mitigators too. Protection and water gathering

for rainwater harvesting. Our place has lots of terrain and

some we can play with for water and fertility capture. Our

market garden site is on a fence line bordering our

neighbours where we share a flat valley floor which in an

ideal world would maybe not be demarcated by ownership or

fences. It is on about a one-degree slope downhill towards

our garden. We installed a swale to feed nutrient and water

into the second hoop house and to establish a line of

mulberries that will shade and drop very nutritious leaves

into the swale for extra downhill nutrition. Swales have

been very successful on other parts of the property

including the first hoop house we built which post rain

event requires only a light watering for even intensive

crops and the fertility is building year after year. Another

swale is being constructed for bamboo and more mulberries.

Micro swales have been included when planting a small

orchard on site too. We have also planned for the top of our

swale to have composting bins that will take any nutrient

run off to the lower part of the garden.

In these zones we are planting trees but moreover

essentially eliminating stock to allow natural growth. They

‘holiday’ there for only around 3 days a year. It is a

‘sweep’ in late summer or autumn for fire control and a

little disturbance which we have found benefits the plants.

Irrigation water for the garden is very minimal compared to

any other operation I know of. Due to water mineralization

problems and the need for conservation of moisture we only

water in the dark hours and at a push late afternoon. Most

is hand watering or spot watering to avoid build up in the

soil of magnesium and other minerals. About once a fortnight

some areas are watered overhead for a few hours in the night

to replenish the deeper soil moisture. We once used T Tape

and similar irrigation which seems to last only a few years

without problems. We have a very lofty ideal of trying to

eliminate plastic from our garden ventures and there are a

lot of plastic irrigation pieces. This past season we hooked

our water line into one of the many dams on the property. It

allowed us to see the fantastic results dam water can bring.

It also gave our soils a rest from the mineralization. An

installation of a 20,000 litre rain water tank and shed

(both second hand) should give us enough water for the

installation of up to 20 wicking beds to further secure our

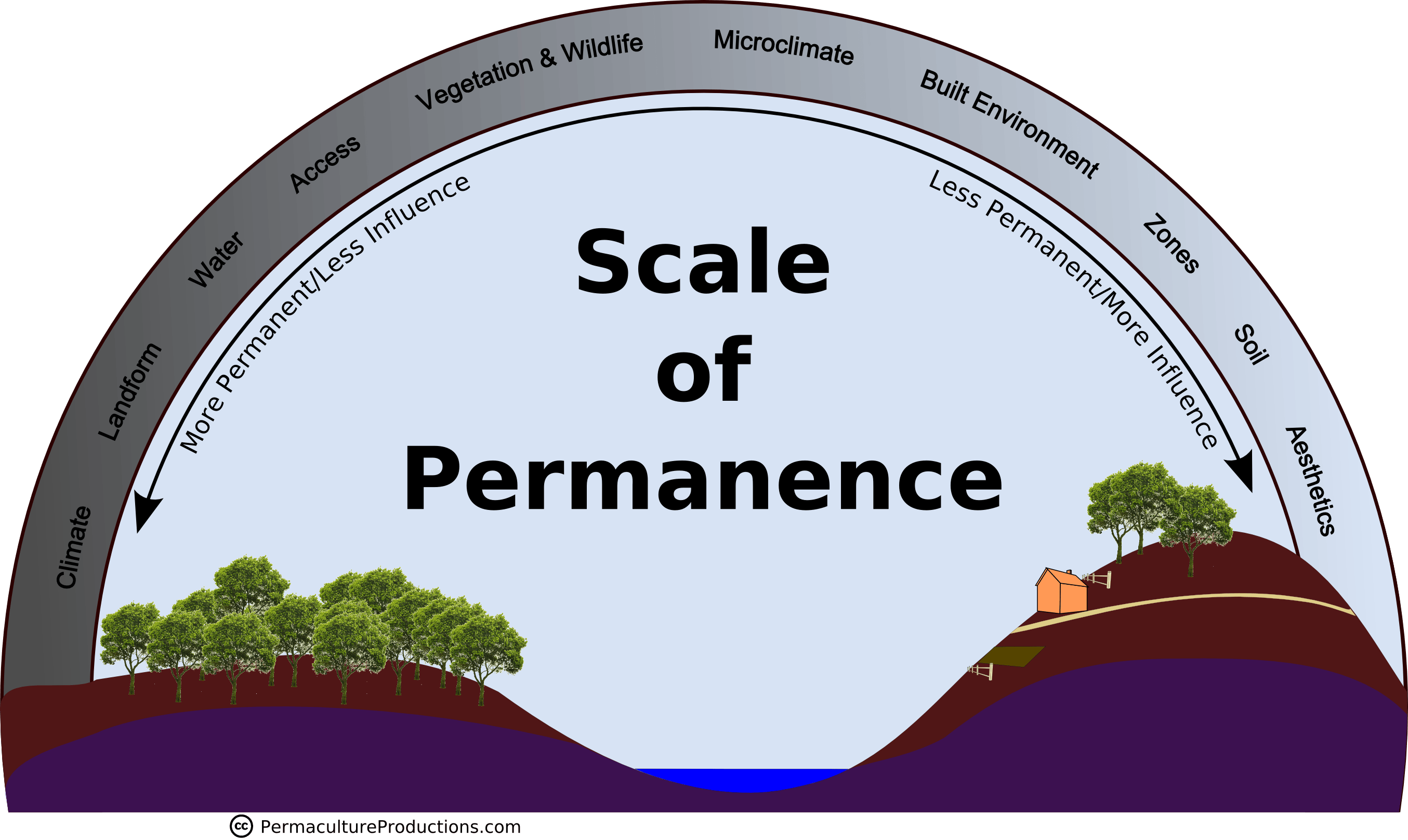

water and climate control. The scale of permanence is a

constant revisit and feedback loop: Apply self-regulation

and accept feedback.

In these zones we are planting trees but moreover

essentially eliminating stock to allow natural growth. They

‘holiday’ there for only around 3 days a year. It is a

‘sweep’ in late summer or autumn for fire control and a

little disturbance which we have found benefits the plants.

Irrigation water for the garden is very minimal compared to

any other operation I know of. Due to water mineralization

problems and the need for conservation of moisture we only

water in the dark hours and at a push late afternoon. Most

is hand watering or spot watering to avoid build up in the

soil of magnesium and other minerals. About once a fortnight

some areas are watered overhead for a few hours in the night

to replenish the deeper soil moisture. We once used T Tape

and similar irrigation which seems to last only a few years

without problems. We have a very lofty ideal of trying to

eliminate plastic from our garden ventures and there are a

lot of plastic irrigation pieces. This past season we hooked

our water line into one of the many dams on the property. It

allowed us to see the fantastic results dam water can bring.

It also gave our soils a rest from the mineralization. An

installation of a 20,000 litre rain water tank and shed

(both second hand) should give us enough water for the

installation of up to 20 wicking beds to further secure our

water and climate control. The scale of permanence is a

constant revisit and feedback loop: Apply self-regulation

and accept feedback.

Looking back on the list in SOP soil fertility, management

(people) and aesthetics are elements that come and go within

a space. They do mostly depend on the people and the ways of

working. The most important asset to a farm is without a

doubt the soil. Without soil health function of everything

else ceases. High profile soil experts such as Nicole

Masters, Dr Elaine Ingram and Matt Powers all run the same

message that soil is number one. Questions could be directed

outwards. Why is it not at the top of the Scale of

Permanence? Well, it something you can change and nurture

and build in a relatively short period of time. The elements

at the top of the list can be worked with in the landscape,

for example, if you don’t consider placement and control of

your landscape changes or water building capacity for a

certain purpose the chances are building the soil and the

overall holistic health of the farm, including the people

are not going to go the distance. Going the distance is a

very high priority! In a year we have produced a whopping 7

tonne of veggies from our garden of under an acre. That’s

right: one acre out of 540. It has fed us veggies and up to

12 boxes per week to our community. Also, it has remade our

compost and been a large part of the diet of our pigs and

chickens. The demand is huge for good clean food grown in a

deliberate system that incorporates natural elements for

longevity for both people and environment. All the hurdles

that we face every day are slowly being overcome, so far

with minimal inputs, that mostly come from the repository of

the whole farm. The most important part though is the care

of not only the environment but the people in that system

and that why our slow and small solutions come to us in a

flow that can’t be rushed. The ideals we have followed

through on from our youth are beginning to pay off. That

nuggety man knew, and many brilliant collective minds know

it works and they are building a better world.

Looking back on the list in SOP soil fertility, management

(people) and aesthetics are elements that come and go within

a space. They do mostly depend on the people and the ways of

working. The most important asset to a farm is without a

doubt the soil. Without soil health function of everything

else ceases. High profile soil experts such as Nicole

Masters, Dr Elaine Ingram and Matt Powers all run the same

message that soil is number one. Questions could be directed

outwards. Why is it not at the top of the Scale of

Permanence? Well, it something you can change and nurture

and build in a relatively short period of time. The elements

at the top of the list can be worked with in the landscape,

for example, if you don’t consider placement and control of

your landscape changes or water building capacity for a

certain purpose the chances are building the soil and the

overall holistic health of the farm, including the people

are not going to go the distance. Going the distance is a

very high priority! In a year we have produced a whopping 7

tonne of veggies from our garden of under an acre. That’s

right: one acre out of 540. It has fed us veggies and up to

12 boxes per week to our community. Also, it has remade our

compost and been a large part of the diet of our pigs and

chickens. The demand is huge for good clean food grown in a

deliberate system that incorporates natural elements for

longevity for both people and environment. All the hurdles

that we face every day are slowly being overcome, so far

with minimal inputs, that mostly come from the repository of

the whole farm. The most important part though is the care

of not only the environment but the people in that system

and that why our slow and small solutions come to us in a

flow that can’t be rushed. The ideals we have followed

through on from our youth are beginning to pay off. That

nuggety man knew, and many brilliant collective minds know

it works and they are building a better world.

... sounds very vague and

generic but I suspect it won’t change throughout my life and

it has been my mantra since my childhood. I, also more

pragmatically, had the desire to concentrate on the elements

of not only my life but our business that would pull it all

together into a tighter knit. I had costed out a market garden

model during the HM course. If we could turn out an average of

30 plus organic but reasonably priced produce boxes into the

community each week, within five years we would be earning a

small income and feeling we are contributing to the health of

our families in the community. A good start. I had learned

from an extended time working with a community of young people

that they, more often than not had households without good

food and had parents who didn’t know how to cook.

Being a gardener since early

childhood (I think I was 3 when I was planting broad beans

with my father) and a permaculture practitioner since my late

teens I thought I had it all down pat. Observe the site, plan

the garden, dig the garden, plant the seeds and in the words

of Neil, my hero from the BBC series the Young Ones; “nature

will grow the seeds” and it does; somewhat. But this is not

Disney nor is it Instagram: it is dance and martial arts.

Spiritually i needed to ‘Obtain

a Yield’ which was needed for our family: for health and

vitality. During the 20 years of free-range pig

farming/marketing and the subsequent toils of a town job the

growth of veggies was small and spasmodic. Ironically in the

years we were delivering produce to Brisbane and Sunshine

Coast our food security went out the window. We were too busy

and too tired for consistency. And to make matters worse

around our Zone One, the possums had taken over, eating

whatever yield we were expecting. For those curious, a Zone

One in a permacultural system design is where you can reach

out your back door and go pick a plenty and you can tend in

detail in your PJ’s if necessary.

See this good resource: https://deepgreenpermaculture.com/permaculture/permaculture-design-principles/4-zones-and-sectors-efficient-energy-planning/

See this good resource: https://deepgreenpermaculture.com/permaculture/permaculture-design-principles/4-zones-and-sectors-efficient-energy-planning/

During our

time with Brisbane deliveries we supplied a few small shops

and co-ops. We grew organically certified market garden

crops that pigs could eat any gluts we had. Most famously

snow peas and rocket which during times of no delivery we

would feed to pigs who relished them. Pumpkin, sweet potato

and zucchini in summer. Limited specific crops. We did do

produce boxes for over a year in that time. This was when it

was still foreign to locals and customers and the boxes were

limited to a few local teachers and artists who had

understood the concept of a mixed box. It is difficult for

the buyer. You don’t know really what you are getting each

week. It doesn’t cater for those people who don’t like to

cook as it necessitates that one must be inventive with meal

planning. What it does do is call for you to be engaged with

your food and seasonality and as Michael Pollen says in In

Defence of Food “eat food; not too much; mostly plants” So

this became my cunning plan: make them cook! Also, from the

farmers perspective wasting the good food that they produce

for no other reason than to cater to recipe whims is

heartbreaking. The food waste, apart from its appalling

total energy loss to the system, seems to be an expected

part of any food production system. Our veggie boxes didn’t

allow for the mass throw-out of unwanted veggies that is

prevalent in many market gardens. The ugly veggies are put

into the boxes as extras. Any other clean veggie waste feeds

our pigs and cows, but mainly ends up in our compost to

direct feed our veggies. Our systems have always endeavoured

to be a tight closed loop with as many inputs as possible

coming from the farm. The Holmgren principle: ‘Produce no

Waste’ is more than just recycling and feeding the waste to

worm farms. It is integral and intrinsically married to the

ecosystems of a farm. We can’t keep taking without putting

energy back into that system. Food is energy and food for

one, is food for another. Our compost is made from the weeds

and grass that are slashed from the paddocks and when

applicable green waste that we shed when packing veggies for

customers. Manure tea is sometimes made with cow manure and

chicken manure (and weeds) fermented in a 1000 litre tote

and aged for safety. This year we had to bring in some

piggery waste as aged compost to use in our compost and on

our beds to boost our nitrogen and phosphorus content.

Included with this compost we were able to see the breakdown

chart, so we were relatively happy with its safety. It was

relatively cheap and clean and taken from intensive weaner

pig pens. Our pigs have never been able to give us a

quantity of manure for the garden as they are free range and

with a healthy quantity of dung beetles, we couldn’t collect

it if we tried except maybe nappies on each pig? Intensive

piggeries are pig gaols of horror proportions. But we figure

us taking a very small amount of their waste and putting it

to good use isn’t going to support that system. When we

started, we started with what we knew. Holmgren permaculture

principles nibbling at the edge of the brain and heart; we

began planning. I was very lucky to be introduced to PA

Yeomans very early on. He explored the idea that you need to

put things in an order of consideration when planning

sustainable land use. Some things cannot be changed, or if

they can, they would cost far too much money to ever be

changed. This is particularly obvious in planning out a

farm. We had little to no capital, like most farmers. As of

writing, the average wage income of an Australian farmer is

around $32,000, so not a lot to throw around. Dave Jacke, an

American permaculturalist adapted from Yeomans, the “Scale

of Permanence” concept (among other great ideas), which

consists of working with the things that can’t be changed

first and incorporating everything else in degrees from the

hardest to the easiest to change. It isn’t a check list that

says you must get this one perfect before the next. It is a

process to consider, understanding that you are imposing

something on a landscape. The more you can work with the

elements that are already there, the better your system will

potentially function with less inputs for the desired

result. Designing from patterns to details.

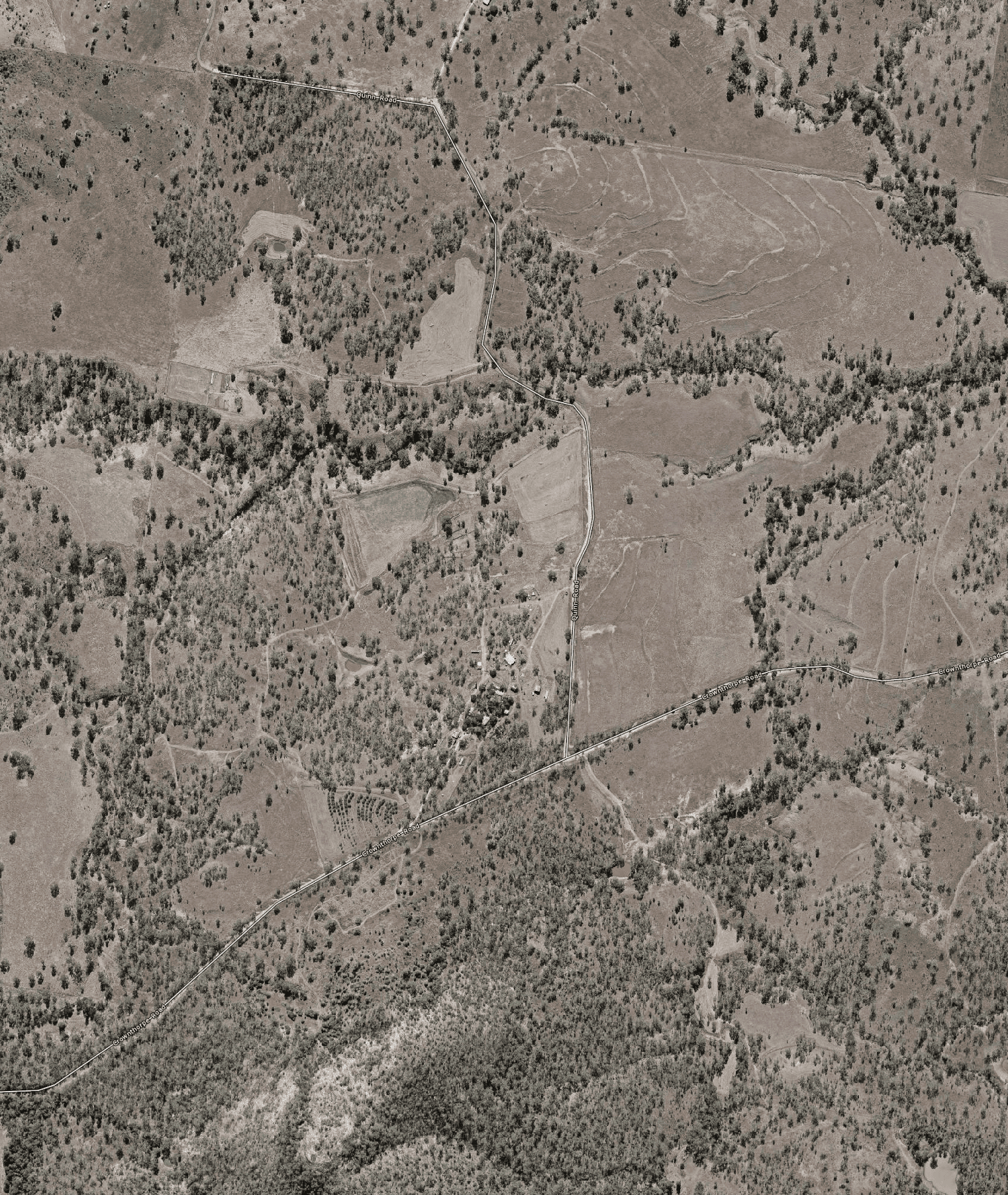

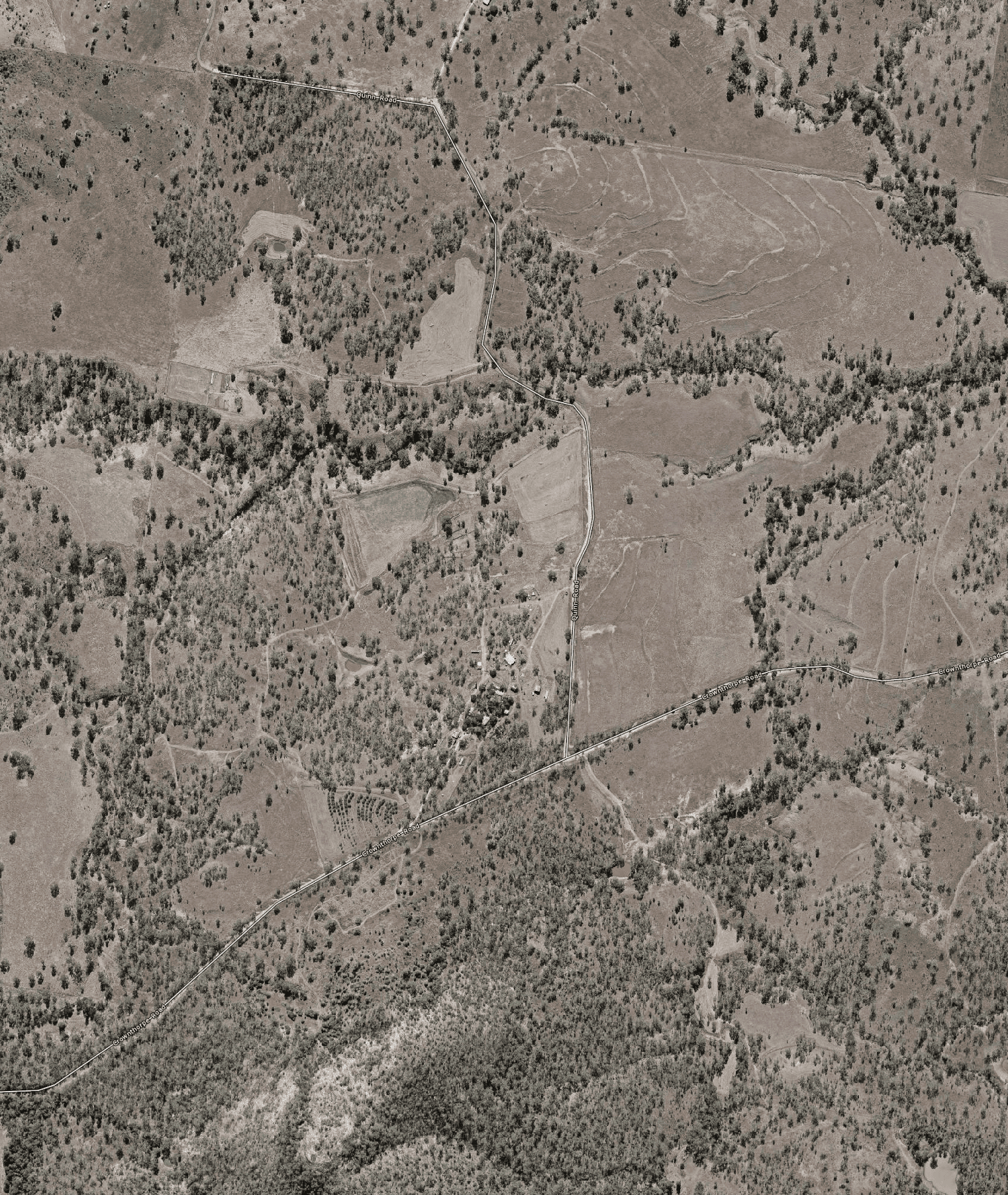

The South Burnett area like

many Australian landscapes that are tired through massive

clearing and intensive farming practices has a scarcity of

good water. Our creek water is ‘salty’. Filled with an

overload of calcium carbonate that has leached to the

surface. A 1950’s aerial photo of our farm shows bare

paddocks, substantial cultivation and moreover a bare

over-grazed creek system. These days our riparian zone is

very protected and has been most of the 30 years we have

been here; increasing by degrees.

We have studied many market

gardeners all over the world who have made some of the

mistakes. Their resilience and ability to use this principle

is very admirable. Most helpful has been a Canadian guy

called Jean Martin Fortier who has a book called ‘The Market

Garden’ available as a very worthwhile audiobook as we read

it while working in the market garden. He has the outlook of

a permaculturist coupled with pragmatism. He taught us about

lots of things but in particular the use of proper access in

the bed system of gardening. His thoughts and experience are

coming from the ideas put across in Christopher Alexander’s

‘Pattern Language’ a permaculture classic regarding creation

of spaces to provide natural flow for human navigation.

Thinking about how you move and to what purpose, can be

built into the design and can mean the difference between

being happy and being so sore and fatigued that you don’t

want to garden the next day. We deliberately (until this

current season) have been very reluctant to make long beds

remembering the long days of walking up and down rows.

There are other ways. We

feel we need to mix crops in together to give extra measures

surrounding pest control, but flow and function is a bit of

a hassle when trying to get enough access to functional

space. Planning production for the veggie box week, etc is

tricky and dancing around this planning can be hard. Access

and circulation in the system is always being fine-tuned.

The larger lane ways and access points for water and

vehicles are designed to be a constant and can’t be changed

and are therefore high on the scale of permanence. Human and

animal walkways can be given a little more leeway. Access to

our compost bays to bring in mulch, tractor access and

access to the shed for construction. These elements must be

permanent within the scope of the project. Vegetation and

wildlife movement are highly active near our market garden.

The main creek and surrounding riparian wilderness zone,

where we promote ecological movement, borders two sides.

This is on our neat quadrant of threats and opportunities

(know the square?) A preparation for battle is always on our

minds and in our work program. The fence surrounding the

garden is strong. The electric fence power is stronger. The

next battlement of a floppy top and bottom added to the

fence and a construction of a full chicken run surrounding

the garden is next on our list of priorities. All mitigation

techniques. Chickens have proven their worth in the garden

area... not the garden itself... the odd renegade is feather

clipped and returned after the usual bout of swearing from

us. When a plague of grasshoppers came in last year, we

fortified the outside with over 40 chickens and over a week

or so, most were gone. They were young point of lays mostly

and smaller chickens, so they learned what great veggies

taste like and are still very excited to seek out grubs and

eat anything. Most animals here have many functions.

Chickens are secured around buildings to seek out white ant

trails, taken to treed areas to fertilise and push down

grass. Where bush land needs fertility and a little

kickstart chickens are introduced for a very short time to

exhibit their natural behaviours and eat insects and larvae.

They follow cows and pigs sometimes to rake over areas where

cows may have dropped ticks and larvae of worms etc. The

importance of timing these events is about observation and

education of the lifecycle of micro fauna and flora. In our

brittle environment a wrong animal in a space can set back

an ecosystem for a considerable period. Gentle watching and

gentle treading.